¶ Portuguese Playing Cards Brought to Japan

The Portuguese first landed in Japan in 1543 on the island of Tanegashima, where they introduced matchlock firearms to Japan. Francis Xavier, a Jesuit missionary and representative of the King of Portugal, arrived in Japan in 1549 to propagate Christianity (Roman Catholicism) to the islands.

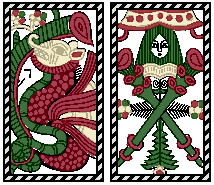

In 1571, Nagasaki was opened as a port for trade with other countries. It is believed that during this time, the Portuguese brought playing cards to Japan, which had only 48 cards and featured dragon designs on the aces. Nowadays, these Portuguese cards brought to Japan were classified as “Nanban Karuta (南蛮カルタ)”, after the term used to refer to the foreign traders, nanban (南蛮, ‘southern barbarians’).

¶ Birth of Tensho Karuta

It was speculated that sometime during the Tensho era (1573-1592), the Japanese started manufacturing their own copies of Portuguese playing cards, which were then simply known as karuta (賀留多), after the Portuguese word for ‘cards’, carta. Nowadays, these domestic products are classified as Tensho Karuta, after the era in which they started to be made.

One of the places in Japan known to produce karuta around this time was Miike Village, Chikugo Province (present-day Omuta City, Fukuoka Prefecture). Japanese literature mentions karuta as a specialty of Miike Village as early as 1638.

In the following years, the Tensho Karuta industry would be affected by two factors:

- The cards were used as a tool for gambling, which is detrimental to public order and frowned upon by the ruling authorities.

- The cards featured foreign designs that could be mistaken for Christian iconography.

¶ Bans on Gambling with Karuta

The early punishments for gambling in Japan can be traced back to 1581, when a Japanese Christian (kirishitan), after failing to keep his pledge to stop gambling, was punished by rope bondage, and a fine of more than 80 Portuguese cruzados worth of rice. However, it is not known if karuta was involved.

In 1591, when Tokugawa Ieyasu and his clan transferred to the Kanto region, he immediately decreed that gambling is punishable by death.

In 1597, Chosokabe Motochika, the feudal lord of Tosa Province (present-day Kochi Prefecture), enacted the “100 Articles of Chosokabe Motochika” in Urado Castle, which issued a ban on gambling karuta games. This is by far the earliest document in Japanese literature where the word “karuta” can be read.

There were many other local bans on gambling with karuta throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), but despite the bans, people continued to play karuta undercover, and karuta became widespread in many provinces in Japan.

Punishments for gambling varied from one domain to another, and tended to be stricter toward the ruling class and more lenient toward commoners. Criminals could be fined anywhere between 2 to 5 kanmon (approximately 60,000 to 150,000 yen today) which has to be paid within seven days, or else they could be handcuffed for a number of days, or sentenced to prison, exile, banishment, corporal punishment, or even death.

There were several documents that describe the punishment for gambling with karuta, as well as accounts of people caught and punished.

In 1683, in Edo, Kichizaemon and Kuzaemon were arrested for gambling with karuta, and were imprisoned for a year and a half, after which they were pardoned.

In 1702, in Edo, Shichirobei Akai Masayuki, a senior official of the front line, was appointed concurrently as a gambling inspector, and during his term, 3 people were executed and 18 were exiled for gambling. This punishment was criticized as being too harsh and severe, and he was eventually dismissed from his position as gambling inspector only 3 months after he was appointed.

In 1742, the 8th Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, ordered the compilation of “Kujikata Osadamegaki (Book of Rules for Public Officials)” which describes the punishment for playing yomikaruta or betting games: 30 days of handcuffs for first offenders, and a fine of 3 kanmon (approx. 75,000 yen today) for repeat offenders.

In 1792, the “Ofu (Owari Province) Criminal Law Rules” was enacted, where repeat offenders of gambling with karuta are punished by 10 days of imprisonment.

In 1806, in Maehakoda village of Takasaki domain (present-day Maehakoda-cho, Maebashi city), Heizō, who was in possession of a set of karuta, was found guilty of playing karuta for a bet of 1 or 2 mon at his home with Toramatsu and Shigeshichi from the same village. All three were made to lie face down in front of the prison and were whipped 50 times on the shoulders, back, and buttocks.

According to Jan Cock Blomhoff’s description in a catalog of his collection of Japanese relics obtained in 1824, those who were caught gambling by the police were beaten with an iron rod 50 times for the first offense, or beaten with an iron rod 100 times and then imprisoned for the second offense, or executed for the third offense.

¶ Bans on Producing and Selling Karuta

With the bans on gambling with karuta imposed, it can be assumed that the production and sale of karuta was also strictly controlled as well. There were many documents describing the prohibition of sale of Karuta.

In 1728 and 1731, there was a law in the Tottori Domain (now Tottori City, Tottori Prefecture) that prohibited the sale and purchase of karuta and dice.

In 1739, an notice was issued in Osaka, ordering all sellers of kingo karuta to stop their business, and those selling openly with a signboard should remove the signboard immediately.

In 1755, sale of gambling karuta was also prohibited in the Kumamoto Domain (now Kumamoto City, Kumamoto Prefecture).

During the Kansei reforms (1787-1793) the ban on karuta was strengthened nationwide.

Because the enforcement was stricter, many karuta shops around Japan, the majority of which were in Kyoto, were not allowed to sell karuta openly in their stores and disappeared during the Kansei era (1789-1801). However, in some areas, the industry continued covertly, operating under a different trade to avoid any crackdowns.

It is worthy of note that the prohibitions on karuta cover only those that were designed for playing gambling games. Because of this, Uta-garuta, such as Hyakunin Isshu, as well as other E-awase type karuta, especially those meant to be played by children, were allowed to be sold openly.

¶ Soured Relations with Christianity in Japan

After Totoyomi Hideyoshi reunified Japan and became its ruler in 1586, he started to become suspicious of the growth of Christianity in Japan. By 1587, after his invasion of Kyushu, he was alarmed by reports of what the Jesuits were doing: they had claimed and garrisoned the city of Nagasaki, forcing commoners to convert to Christianity, taking and selling non-Christian Japanese from the port as slaves, and allowing the slaughter of horses and oxen for food, an offensive deed to Buddhism.

Later that same year, Totoyomi Hideyoshi promulgated the Bateren Edict, aimed at expelling any Christian missionaries in Japan due to their clear violation of Buddhist law, prohibiting the slave trade, and promoting freedom and respect of all religions. While Hideyoshi was successful in taking back Nagasaki from the Jesuits, the edict was not strictly imposed, and missionaries still kept preaching openly around other parts of Japan.

Then in 1596, The Spanish ship San Felipe was shipwrecked on the island of Shikoku, where the local feudal lord Chōsokabe Motochika seized the cargo of the ship and escalated the incident to Totoyomi Hideyoshi. Hideyoshi then learned from the pilot of the ship that it was Spain’s plot to infiltrate countries with missionaries before an eventual military conquest. He also learned that the Philippines and several countries in the Americas were colonized by the Spanish after converting their inhabitants into Catholicism.

Hideyoshi was furious upon this revelation, and in 1597, Hideyoshi paraded and executed the 26 Martyrs of Japan by crucifixion, the first lethal execution of Christians in the country. The persecution of Christians continued until his death in 1598.

¶ Ban on Christianity and Beginning of Sakoku policy

When Tokugawa Ieyasu assumed power following Totoyomi Hideyoshi’s death, he initially gave priority to trade with Portugal and Spain. While he did not like Christianity, he tolerated it to a certain degree. Meanwhile, Dutch and English traders, in an attempt to take away control of trade with Japan from Portugal and Spain, advised Ieyasu that those countries indeed had territorial ambitions, using Christianity as their means to control the inhabitants, and that the Dutch and English promised that they would never conduct any missionary activities in Japan and would only focus on trade.

In 1602, Tokugawa Ieyasu issued an edict banning Christianity in Japan and ordering the destruction of Christian churches, claiming that Christians are bringing disorder to Japanese society. This was effective throughout the entire Edo period (1603-1868). All Japanese were required to register at a Buddhist temple, which became an annual requirement. Moreover, all European missionaries were expelled, and all Christian converts were executed, marking the end of open Christianity in Japan.

In addition, after Ieyasu became a Shogun and established the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603, the Shogunate imposed foreign trade policies around the 1630’s (now known as Sakoku policy) which severely limited trade between Japan and other countries. During this time, the only westerners allowed to trade with Japan were the Dutch, effectively eliminating any colonial and religious influence of Spain and Portugal.

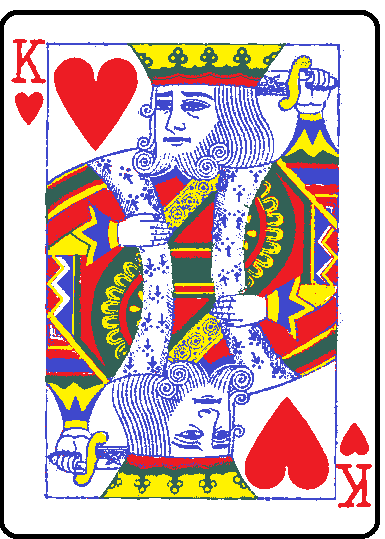

¶ Oranda Karuta: Dutch Playing Cards

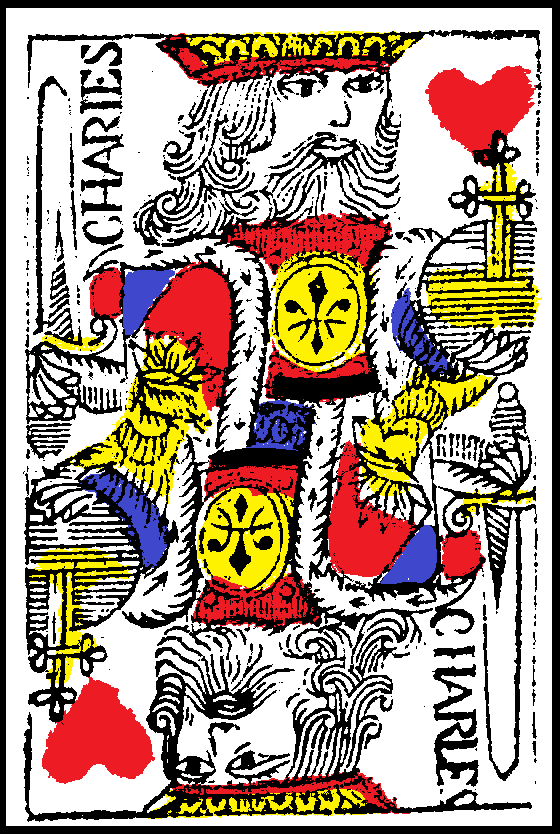

Even before the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603, the Dutch had already been trading with Japan since 1600, with formal trading relations being established in 1609. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch also brought playing cards made in the Netherlands to Japan. They were straightforwardly called Oranda Karuta, which literally means “Holland playing cards”.

Unlike the 48 card decks of the Portuguese, these Dutch cards contained 52 cards per deck, and featured french suits just like modern western playing cards.

While there were many accounts of these decks being brought to Japan and being played there, almost no accounts of Japanese copying this design exist, especially on a massive scale intended for sale. Very few physical relics of Dutch-made playing cards in Japan from this era exist today.

It is thought that the game E-tori was originally played using these decks.

¶ Hayashi Shihei’s Oranda Karuta (阿蘭陀加留多)

It is said that Hayashi Shihei, a Japanese military scholar and a retainer of the Sendai Domain, has taken advantage of his position to visit Nagasaki three times since 1775. From there, he bought the Dutch card deck, along with a deck of Chinese money-suited paper cards, and gave them as a gift to his friend Fujitsuka Shikibu, who was a Shinto priest at Shiogama Shrine.

Remains of a Dutch-made playing card deck (Two cards: A Jack of hearts and a 9 of spades, both bearing designs resembling those made during the late 18th century) became an exhibited item at the Hayashi Shihei Memorial Exhibition at the Sendai City Museum. Currently this is the only physical evidence of Dutch playing cards coming to Japan before the Meiji period that exists today.

¶ Udagawa Yōan’s copy of Oranda Karuta (和蘭闘牌)

When Jan Cock Blomhoff, the director of a Dutch trading colony in Nagasaki called Dejima, arrived to Japan for the second time in August 1817, accompanied with his wife and son among other people, he brought with him twelve types of toys, one of which was a deck of playing cards.

Udagawa Yōan, a Japanese scholar of Western studies who had a close relationship with Blomhoff, knew of these “twelve rare toys” and copied some of them. The “Dutch cards” in particular were copied in his room on April 10, 1821. The copy survived a fire in 1834 and was handed down to the descendants of the Udagawa family. A replica of this deck, which was reprinted at Nintendo by the Rangaku Materials Study Group, can be found at the Tsuyama Archives of Western Learning.

While the copy of the deck exists today , the original Dutch-made cards were nowhere to be seen, probably because they remained in Blomhoff’s possession when they were deported away from Japan.

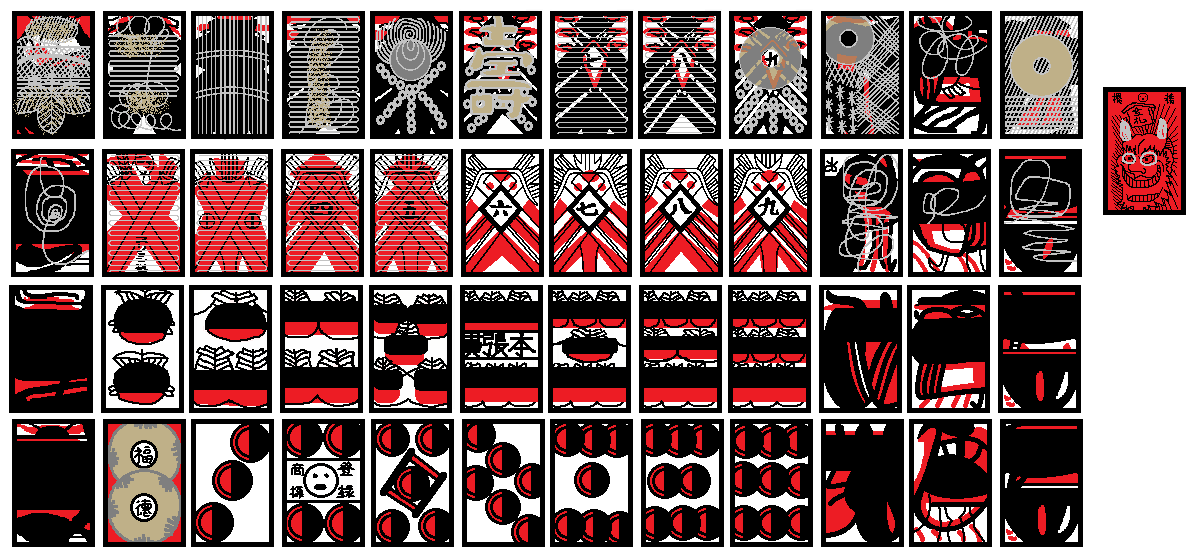

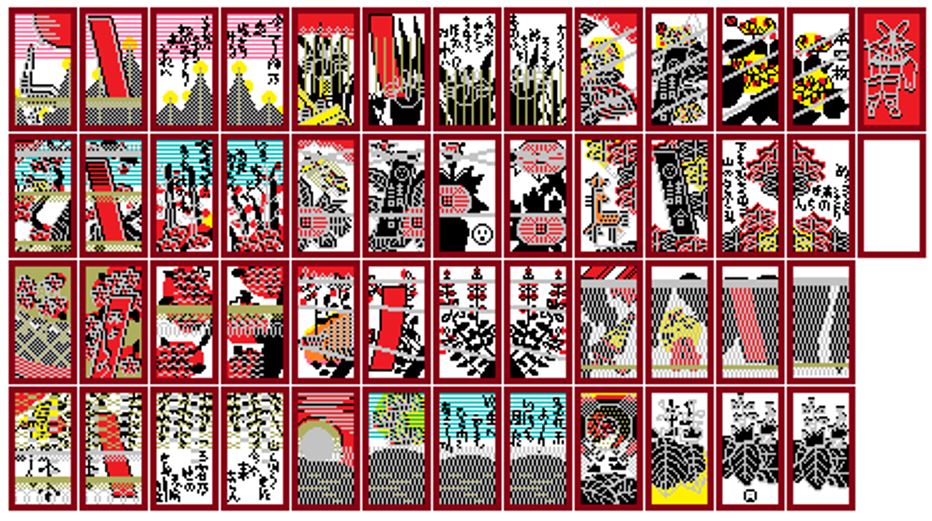

¶ Evolution of Tensho Karuta into Mekurifuda

Due to the ban on Christianity, local karuta manufacturers became wary of the designs on the cards, which featured foreign imagery that could be mistaken for Christian iconography, especially the suit of cups which looked like the Holy Grail. A person owning a Karuta deck could be accused of being Christian and executed. There was even a humorous account of this in a collection of Japanese stories in 1749, where Shigeemon of Hatchobori, Edo, discovered a piece of karuta in the Buddhist altar of his tenant Rokubei, and caused a big commotion by quickly assuming that Rokubei was a Christian. The story later goes on to describe how Shigeemon was punished for committing a crude offense because he did not know about karuta.

Considering this, it appears that karuta manufacturers tried to cover up or change the foreign iconography of Karuta. They replaced the courts with illustrations suitable for Japanese tastes, such as images of Samurai or Buddhist iconography. Eventually, manufacturers heavily overprinted them with color or transformed them into abstract shapes or strokes which sometimes resemble Japanese characters, likely as a way to speed up the production process and to reduce costs.

Also, the cards were made to be smaller than the Portuguese cards they were based on. It was initially thought to be an adaptation of a practice by the Portuguese traders to cut the edges of the cards and wrap them with backing paper once the edges started to wear out, but this is untrue. Nowadays, it is thought that the change in dimensions was likely to make the cards easier to be carried and held by Japanese hands.

Originally, each manufacturer created their own designs of karuta, and copying the design of another karuta manufacturer was prohibited; however, during the bans on public sale of karuta, the practice of copying the designs of other manufacturers occurred very often, since manufacturers could not claim copyright on illegal products such as karuta. It is also possible that when a karuta manufacturer producing a popular design suddenly closed, other karuta manufacturers would copy that design to take over their market.

The resulting Karuta decks slightly varied in design and structure depending on the manufacturer, the region in Japan it was made, and the kind of game that was popular in those regions. These types of cards were given various names based on the games played with them, such as “Tensho Karuta”, “Yomi Karuta”, “Mekuri Karuta”, “Kingo Karuta”, “Kabu Karuta”, etc., but because of the similarities in their structure and design, they are now all classified as Mekurifuda.

There are several written documents mentioning the specific name of karuta that was played.

In 1739, an notice was issued in Osaka, ordering all sellers of kingo karuta to stop their business, and those selling openly with a signboard should remove the signboard immediately.

In 1742, the 8th Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, ordered the compilation of “Kujikata Osadamegaki (Book of Rules for Public Officials)” which describes the punishment for playing yomikaruta or betting games: 30 days of handcuffs for first offenders, and a fine of 3 kanmon (approx. 75,000 yen today) for repeat offenders.

The “Shinban Kaiban Oharaigawa” published in 1789 mentions the name “Tensho Karuta”.

In “Bakugi Saisho (‘a detailed look on gambling’)” written by essayist Yamazaki Yoshishige sometime in the Bunsei era (1818-1830) , the following is explained about “Tensho Karuta”: " These are 48 karuta cards that are still in use today. The first card, called Tensho, is especially beautifully colored, and has the characters “Tensho Kin-iri Gokujo Shiire (天正金入極上仕入, ‘Tensho with gold, finest purchase’)” written on it, so it is known to the world as Tensho Karuta. The way this karuta was played in the past is different from how it is played today. In the past, it was used to play a game called “yomi”, but later, a game called “mekuri” was played. Cards were dealt to the people, and the remaining cards were stacked and placed face down. Players would draw them one by one and match them with the cards they had in their hands, and the winner is determined."

¶ The Origins of Hanafuda

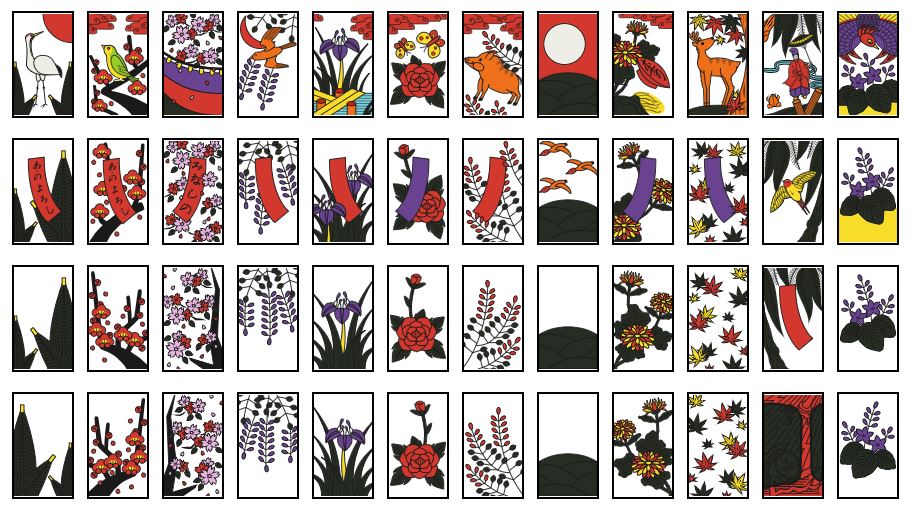

The earliest ancestor of hanafuda can be traced back to the Genroku era (1688-1704), with a type of e-awase karuta called Hana-awase Karuta.

Each set contains 400 cards. 100 types of flowers were featured, with each flower appearing in 4 cards. Of those 4 cards, one of them also featured an object or an animal, which is usually a bird (and sometimes the color of the card is different), one of them also featured a tanzaku strip, and the other two featured only the flowers.

These early sets had images that were beautifully painted individually by hand in great detail and color, making these early hana-awase sets a luxury item played only by the noble-class Japanese.

Hana-awase karuta continued to be made from the Genroku era up until the early Meiji era (1868-1912). Contents varied from one set to another. Some sets have a different assortment of flowers. Some sets featured different objects and animals, or different assignments for the objects and animals. Some sets did not have the tanzaku strip card. In some sets, not all 100 types were flowers; some of them were different things of nature, such as rocks, mountains, fruits, vegetables, etc (Takashi Ebashi refers to these sets as Kacho-fugetsu Awase).

¶ Transformation from Hana-Awase Karuta to Hana-karuta (Hanafuda)

It is not exactly known when the 400-card sets transformed into the current 48-card set. It was thought that it occurred during the middle of the Edo period, probably during the Kyoho era (1716-1736).

It was theorized that during this time, 48 cards featuring 12 flowers were taken from the 400-card set, and were used to play a gambling game. Because these 48 cards wore faster than the other cards and they had to be replaced, manufacturers eventually sold sets featuring only those 48 cards.

Eventually, to speed up production and reduce costs, these reduced hana-awase sets would be manufactured using woodblock printing and stencils, instead of being meticulously painted stroke after stroke. Surviving examples of these decks were refered to as “Musashino” (武蔵野), which was what was written on the lid of the storage box. They were believed to be made as early as the Meiwa era (1764-1772).

Echigo-bana, a regional hanafuda variant from Echigo province (now Niigata Prefecture), retained the characteristics of the old Musashino designs.

These early 48-card sets already featured all 12 flowers that appear in modern hanafuda, as well as all the objects and animals except for the lightning card. Japanese poems are featured on some of the junk cards, giving the set an elegant literary touch.

It was theorized that the poems were added to disguise the deck, which was used for gambling, as an uta-garuta deck, which was not used for gambling. During this time, uta-awase sets featured two subsets: one set containing the first half of the poems, and the other containing the second half. Musashino cards containing poems also follow this format: the first half of the poem is on one junk card, and the second half of the poem is on the other. However, there were no historical evidence of “hana-awase karuta”, “hana-karuta” or “Musashino” being banned during the Meiwa era.

Toward the end of the Edo period, tastes have changed, and poetry fell out of fashion among the people of Edo, which became Tokyo. This had an effect on the designs of the cards. Poems were removed, and some decorative elements of the cards were changed. However, derivative designs based on the original Musashino design survived elsewhere in the country, and evolved into various regional hanafuda variants known today.

Then in the early days of the Meiji era (1868-1912), the current design of hanafuda, known as hachihachi-bana, was created in the red-light district of Yokohama. After the ban on selling karuta was lifted, the game hachi-hachi became popular, and Kyoto manufacturers started using the hachihachi-bana pattern as well, making it the standard design for hanafuda in Japan even to this day.

¶ Bans on Gambling with Hana-awase / Hanafuda

The authorities have started to notice hanafuda as being used for gambling as early as 1807, in an imperial decree that was issued in Nishimurayama (now Yamagata Prefecture). It states that “Hana-karuta” was being played during the New Year holidays, and that it should be noted that it was known to be used for gambling, despite being a game also played by children, and it also requests the people to stop playing with Hana-karuta immediately.

In 1842, A Kyoto town notice states, “Hana-awase, E-sugoroku, and [Juroku] Musashi are used for the amusement of women in early spring, but gambling with them is prohibited”.

In 1837, Kitagawa Morisada, a historian on customs and manners, wrote the 28th volume of the magazine “Morisada Mankou (守貞漫稿)”, describes “hana-awase” as a game using small cards with images of cherry blossoms, plum blossoms, paulownias, chrysanthemums, irises, etc. painted on them, and that sometimes they were used for gambling.

In 1844, in the Owari Domain (now Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture), a notice was issued to the village which states, “It is not permitted to sell karuta cards used for gambling. Recently, a type of karuta called “Hana-awase” have been sold, and it has been heard that people naturally use them for gambling, which is concerning. From now on, except for the Hyakunin-Isshu uta-garuta that has been around for a while, it is not permitted to sell any karuta cards with the name “Hana-awase” or similar.”

There was a record of an arrest in 1852 in the Moriyama Domain (now Koriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture) for gambling using “Hana Mekuri”.

¶ The End of Sakoku policy and Birth of the Meiji era

After the Meiji restoration in 1868, initially the ban on playing and selling gambling karuta continued. However, in response to Britain’s request for the elimination of non-tariff barriers in an attempt to overcome the slump in trade with Japan, the ban on selling karuta was consequently lifted in the following years.

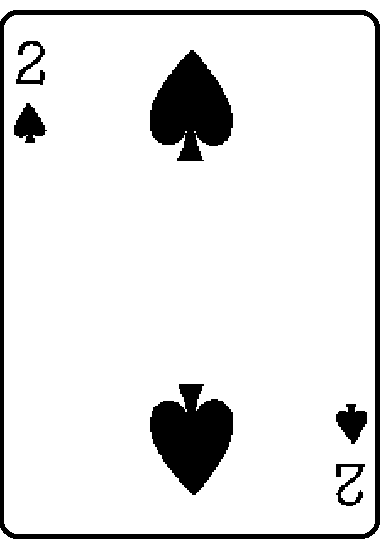

This time, a different type of western playing cards featuring French suits were being brought to Japan by Britain and the United States. As early as 1879, rules for playing games with western playing cards were published, translated into Japanese.

In 1885, a company named Dandansha began importing and selling western playing cards.

The cards were called by several names which did not stick. At first it was called by the strange name Seiyō karuta (“western karuta”), then Toronpu (“trompe”) or Toranpu (“trump”) and Pāsu or Pā (“pas”).

In 1886, Maeda Kihei established Kamigataya in Tokyo and started openly selling Japanese karuta and western playing cards. He even promoted his shop through advertisements in newspapers. By the 1890’s, Kamigataya used the name Toranpu in an instructional book distributed to promote the sale of karuta. The term became commonly used and it stuck, and to this day, western playing cards are always called Toranpu in Japan.

Following these events, all the existing karuta manufacturers that had been producing and selling karuta undercover started selling openly, one by one. They even registered their businesses to prove its legality.

Despite the legality of sale and use of karuta and playing cards in Japan, the act of gambling continues to be banned in the country even to this day, with only a few exceptions, such as government-run lottery, betting on horse-racing or other types of sports racing, and pachinko parlors.

¶ Local Manufacture of Trump in Japan

In 1902, Yamauchi Nintendo (now Nintendo Co., Ltd.) started sales of western playing cards that were domestically produced in Japan. It is thought that Toyo Printing, which is owned by Cigarette manufacturer Murai Bros. & Co., bought second-hand playing card printing machines from Perfection Playing Card Co. and produced the playing cards for Yamauchi Nintendo. However, a different printing company named Watada Printing Co. Ltd. mentions in their company history that in 1902, they produced western playing cards for “Nintendo Koppai” using copperplate printing technology.

There was a story that the first Japanese-made western playing cards were sold by Nintendo in an effort to comfort the Russian POW’s during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. However, Takashi Ebashi stated that he had seen playing cards made by Yamauchi Nintendo in the USPCC Museum (which closed sometime before the transfer of USPCC’s factory from Cincinnati, Ohio to Erlanger, Kentucky in 2009), which were collected by USPCC in 1903- a year before the Russo-Japanese War even started.

¶ Bibliography

- https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/天正かるた

- https://l-pollett.tripod.com/cards37.htm

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/1-2-4-0-jan-cock-blomhoff-two/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Xavier

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Felipe_incident_(1596)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirishitan

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/3-3-2-1-flowercarta-tosamitsunari-genrokuera/

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/3-3-2-2-flowercarta-onehundredflower-suitmarks/

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/3-3-3-2-flowercarta-older-younger/

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/3-3-3-3-flowercarta-origin-musashino/

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/3-3-3-4-flowercarta-musasino-namer/

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/6-2-2-3-kantohanahudacarta-delation-wakapoem/

- https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/トランプ

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/1-1-3-1-dutchcards-udagawa-youan/

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/1-1-3-2-dutchcards-hayashi-shihei/

- https://twitter.com/gelcyz/status/1401543909868642305

- https://www.city.sendai.jp/museum/kidscorner/kids-08/kidscorner-06/kids-38.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hayashi_Shihei

- https://japanplayingcardmuseum.com/1-1-5-1-american-british-earlymeijiera/

- https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/opening-to-japan#:~:text=On July 8%2C 1853%2C American,Japan and the western world.